This article shows some of the complexities involved in dealing with pure lime mortars.

-- A refreshing perspective for residential owners of historic brick / stone homes -- when you're the one footing the bill, not the government. --

.

Monday, November 17, 2014

A drawing from circa 1895

Tuesday, November 4, 2014

Is it wrong to be using Portland cement in an historic mix?

We tend to hear that it is very important to use a lime-only mortar on old brick homes.

But so many properties get repaired with a masonry cement mix that I’d say the message has definitely not been getting across.

And as the result in these cases is an incongruent mortar repair, the loss of heritage character — in other words, the aesthetics — in my opinion, is an even bigger issue than the potential impairment of the structural integrity.

“Portland cement” is a man-made product which is manufactured from limestone and clay and subjected to high temperatures in the firing process which causes it to harden under water and become very dense and hard once set, unlike lime, which remains soft and porous. For our purposes, it is used in addition to lime in a given mix, and not by itself. Sand has to be added.

“Masonry cement” is a preblended mortar mix commonly used in modern masonry construction. It contains a large proportion of portland cement, as well as ground limestone and other chemicals to make the mix easier to work with. It is not required to contain lime, and for this very reason seldom does. It is used by itself, with only the addition of sand. This product should not, in my best professional opinion be used on an old structure, typically pre-1940.

To go back to my contention about purism, it is very difficult to be working with a lime mortar in the same, exact way it used to be done back in the day, here in Canada — assuming you'd be doing it largely for sentimental reasons. If you do it for structural reasons, it is fine to use a lime-only mortar, but understand that it requires much more care (which translates to added costs) in order to ensure that the replacement mortar will not turn to powder after the first winter.

If you’re in doubt, particularly if the building has historic import, by all means, be on the safe side and use a lime-only mix (which doesn't have to be a pure lime mix, as will be explained below).

But if the budget is simply not there, I would rather see a lime-cement-sand mix used that matches the original mix exactly in appearance, rather than a masonry cement mix which makes the repair look like an abortion.

In a lime-cement-sand mix (which is also referred to as a “gauged” mortar), lime is used, typically in a ratio of two parts lime to one part Portland cement (not masonry cement) — although there are other possible variations.

This type of mix does not require so much preparation and care in the application, and has been recognized as appropriate for use in historical buildings.

“U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Technical Preservation Services Preservation Briefs, http://www.nps.gov/tps/".

This document endorses the use of a lime-cement-sand mix to restore old brick structures.

They show the link on this page of their site.

(Furthermore, the picture on the right side of this page on their site features one of the projects that we have performed through their Grant Program.)

Much of Cabbagetown and other enclaves of Victorian homes in Toronto would benefit from a lime-only mix, as that constitutes what has been used in their construction. But a gauged mix is still much preferable to the all-too-often used masonry cement mix.

Again, I’d argue that the quality of the visual match of the replacement mortar is the more important issue to weight in the balance. And that element can be achieved by a skilled applicator with a lime-cement-sand mix, which is not the case, from what I’ve seen, with a masonry cement mix. And keep in mind that many old neighborhoods in Toronto were built using a gauged mix in the first place, such as most of the Annex, for example.

When you see an Edwardian, or Post-Edwardian building in Toronto, it is most likely a fact that the mortar that was used in its construction contains a portion of Portland cement.

Back in 2004, I have spent much time in the archives section of the Toronto Public library, reading masonry trade publications of the 1880’s, up to about 1930, and plotting the dates of various articles and commercial ads found inside against a timeline, which conclusively corroborates the fact that Portland cement was already in use at the time of the construction of many of Toronto’s neighborhoods, such as the Annex, Parkdale, High Park, parts of Rosedale, etc., as mentioned above. The ads in one of the publications even list the addresses of some of the locations in Toronto which were selling the product at that very time.

Regarding the issue with the use of lime, there are two types of lime essentially, a pure calcium lime (sometimes with magnesium too), and an hydraulic lime, which contains clay as an impurity imparting it with a quick set, similar to a cement. The pure lime makes a relatively soft mortar and requires a huge amount of preparation. Both types of lime risk to fail unless a rigorous regimen is followed, for which, at my company, Invisible Tuckpointing Ltd., we charge extra, when a particular building requires their use (for example, we repaired one of the last few Georgian house to remain in existence in the city and we used a lime-only mortar in its restoration).

It happens that a lot of the information that is currently in circulation in Canada about heritage work comes from England. A prominent British expert of the restoration trade is advocating the use of hydraulic lime in restoration, even where cement + lime had been used originally, as he explains that modern Portland cement is much harder that it was over 100 years ago. But hydraulic lime wasn’t used in North America at the time when England switched from a pure calcium lime to hydraulic lime. It was never used here. Instead, the United States and Canada used Portland cement with lime (and even without!) at that time, which was not only manufactured locally, but also imported, as the German version was known to be superior. As well, a natural form of Portland cement was in widespread use, called Rosendale Cement, due to the presence of a large deposit in upstate New York.

After having weighed the pros and the cons, and after having debated many options, such as using Rosendale cement (which is rare and expensive), I do not feel that hydraulic lime always is a better choice, for the reasons given above, as it still requires much added work to ensure the work will last, and many residential homeowners will not want to pay the added cost, instead resorting to hiring lower-priced contractors who will have no qualms about using a masonry cement mix.

The following was taken from an article I wrote close to 10 years ago that was featured in Masonry Magazine:

“Portland cement, the chief ingredient in today’s masonry mortars, sets by adding water, which is called a hydraulic action. Using a quite different process, lime sets over time through a reaction with air, called the carbonation process.

Limestone, chalk and seashells are essentially calcium — calcium carbonate to be precise. Lime is derived from heating limestone (or chalk or sea shells) at high temperatures, which drives off the carbon dioxide that is part of its chemical composition and turns the limestone into quicklime, or calcium oxide.

When water is added to the quicklime, it generates heat, called an exothermic reaction. In the trade, we call this process “slaking” the lime. If the lime is made into a powder at this stage, it will become the lime you may have seen sold at masonry supply stores, called hydrated lime. However, if you add excess water during the slaking process, the lime will turn into putty. (To some confusion, hydrated lime and lime putty are chemically almost the same, and both are referred to as “calcium hydroxide.”)

The longer lime is left as putty, the more workable it will be in the end. Over time, the lime putty undergoes a process whereby the lime crystals reduce in size upon aging and transform into small plates that slide when rubbing against each other. This action allows more water to be absorbed, giving lime the property of being highly workable, or having “plasticity.”

While Portland cement hardens due to the chemical reaction with the water, if stored in a sealed container, lime putty will remain workable and soft indefinitely. Lime will harden over time only when it comes in contact with carbon dioxide and moisture.

Once a lime-sand mortar is mixed and placed in the wall, the water will begin to absorb or evaporate and the mortar will appear to set after several hours. However, the lime then begins to react with the carbon dioxide present in the air and harden, a process that actually will take years to complete. A simplified explanation is that, chemically, the lime is returning to its former state of being a stone.

A more complex explanation is that the carbon dioxide and moisture convert the lime on the surface of the joint back to calcium carbonate. The open pore structure of the lime-based mortar allows the carbonation process to take place deeper in the joint over time.

When tackling a job that requires a straight lime-sand mixture, some experience — at the very least, some caution — is preferred. If the correct application method is not followed, the mortar could soon fail, literally turning to powder.

First, the wall must be kept damp for several days after the lime-sand mortar is applied so that the carbonation process has the necessary time to start before the wall is allowed to dry out. As mentioned earlier, lime mortars can appear to have set. If you are tricked by this and allow the mortar to dry too quickly, it will not have fully started its reaction with carbon dioxide present in the air. With a lack of moisture causing an abbreviated carbonation process, the lime mortar will be so weak that harsh winter conditions could be sufficient enough to make it fall out as early as within the first year.”

- -the more historic significance is assigned to a particular heritage building, whether designated or not, the more care should be taken to ensure that it be properly looked after. And by corollary, this means a higher investment.

- -the last thing it should be repaired with is masonry cement (which typically says Type “N” or Type “S” on the bag).

- -beware if someone offers to use a lime-only mortar on a low budget, as chances are they will not be willing to put up burlaps and keep the wall moist every few hours for 5 days, for example, and without such care the work will be in real danger of failing after the first winter.

- -you’d be better off, in my opinion and experience, if there is no real budget for an historic restoration-type of specification, to opt for a lime-Portland-sand mix which is soft enough to not damage the bricks (usually Type “O”, or even Type “K”), and which has been applied so skillfully that it matches invisibly with the original.

- Below are two relevant ads, as well as one article taken from two different 19th Century trade publications from 1892 and 1895:

Thursday, January 9, 2014

Purism is not for residential heritage masonry

In my opinion, a heritage masonry restoration project should be done in a viable way for the benefit of the structure; but purism is out of reach, unless one has really deep pockets and is being sentimentally inclined.

I’ve once met a man who, having reportedly just spent $920,000 to fix the inside of his house, told me: “When it comes to the outside, I get the restoration boys to do it my way”. And the eventual result was plain awful.

The type of heritage project result that is many notches up the purity scale is usually only done on serious landmark buildings, as it generally costs in the six figures for a building of comparative size to a residential home. And even then, there always seems to be some compromise, one way or the other, in the end.

Over a decade ago, I was pushing to sell such spec in earnest, but *never* had a taker. No one, in the residential arena is willing to push it that far. I’ve actually had several wealthy — two of them prominent — individuals tell me that all they wanted was a reasonable, minimally viable standard, to paraphrase them. And I was told that the money otherwise would rather be donated away to charity before spending it to “that” degree on restoring that particular individual’s house.

The type of heritage project result that is many notches up the purity scale is usually only done on serious landmark buildings, as it generally costs in the six figures for a building of comparative size to a residential home. And even then, there always seems to be some compromise, one way or the other, in the end.

Over a decade ago, I was pushing to sell such spec in earnest, but *never* had a taker. No one, in the residential arena is willing to push it that far. I’ve actually had several wealthy — two of them prominent — individuals tell me that all they wanted was a reasonable, minimally viable standard, to paraphrase them. And I was told that the money otherwise would rather be donated away to charity before spending it to “that” degree on restoring that particular individual’s house.

Such spec would require an advanced mortar analysis to be conducted in a lab at a cost ranging from $2,000 to $3,500 to get instrumental testing done, such as polarized light/thin-section microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, atomic absorption spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, differential thermal analysis, and more.

Following that would be an extensive research to source out, from various material libraries across North America, and re-create the exact sand, and precisely determine what the binder needs to consist of and what the additives actually need to be. This step alone is very time-consuming, and therefore expensive.

Each type of sand would have required a minimum investment of $5,000 at the time, to import into Canada, plus storage costs of $200/month. And it still would not have been a perfect match, at least in the majority of the projects.

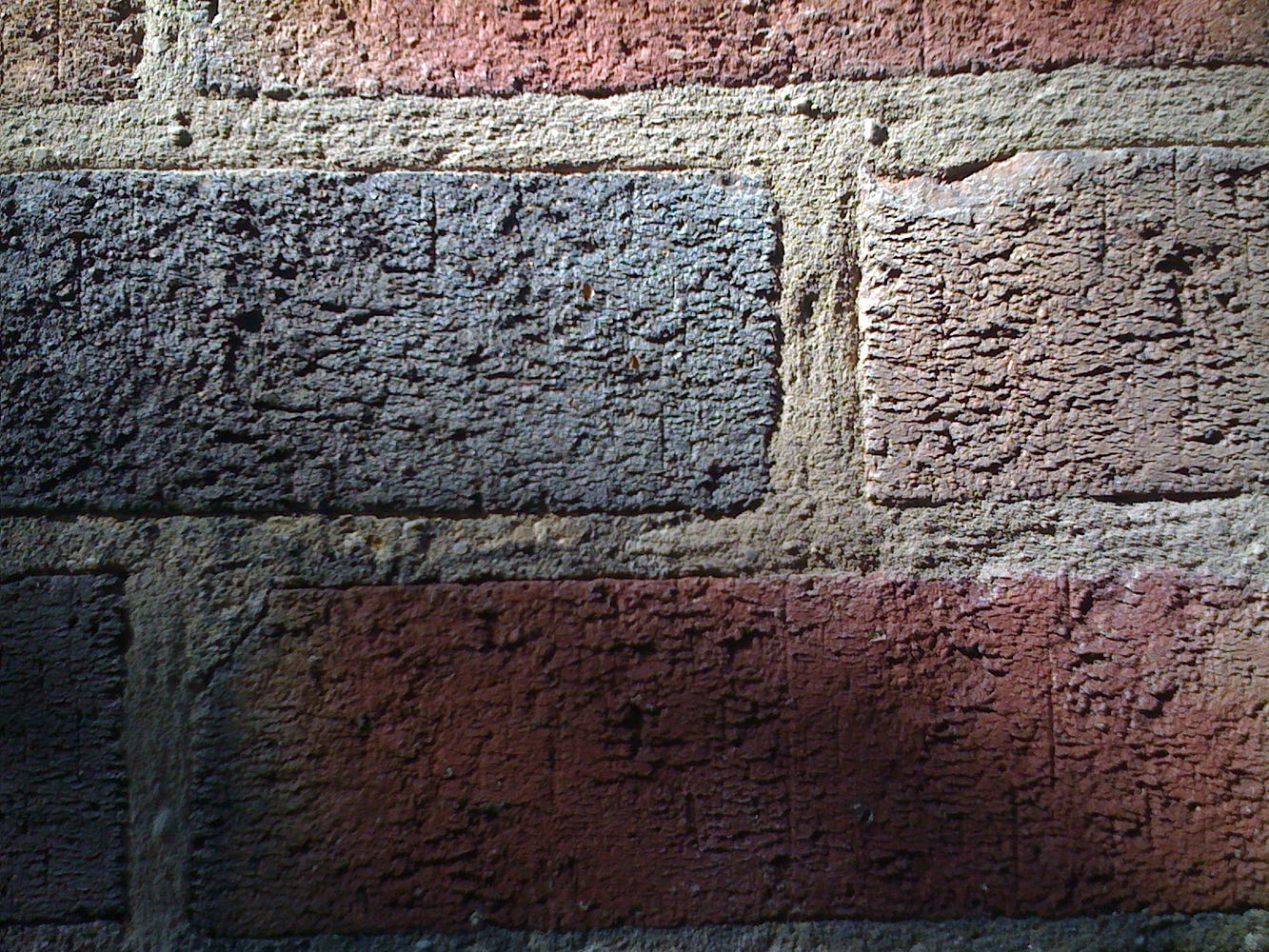

In the case of my company, Invisible Tuckpointing Ltd., which performs repointing services (also known as tuck pointing), as well as brickwork / stonework restoration, customers, including Toronto Preservation Services are more than satisfied with a “close enough” approximation as I’m doing by a “mix and match” approach of various locally available sands, based on a simple mortar analysis, generally conducted by crushing a sample taken from of the house and even dissolving it in acid. And everyone I know in the restoration field uses sands exactly as I am using, and mixes and matches them as best as can be done so as to approximate the in situ mortar — if they bother at all. The following picture features one of my matches, wherein some of the mortar is original, and some we’ve replaced. Can you tell them apart?

Furthermore, the lime (calcium hydroxide) would need to be prepared by acquiring quicklime (calcium oxide), a material now classified as hazardous, and slaking it (adding water to the quicklime so as to create an exothermic reaction) by concurrently adding sand along with the water so as to create a “hot mix” which is what would introduce little chunks of of unslaked lime, similar to those most likely found in the existing mortar on your house. This would require a substantial amount of testing and sieving, and retesting so as to achieve just the right ratio of lime chunks. In other words, simply using lime in the form of a bagged, ready-to-use product (even if its benefits as a hydraulic lime are being highly praised) would not be a puristic way to proceed.

Personally, I’m an advocate of aiming for an aesthetically pleasing restoration of vintage brick or stone buildings using compatible materials, with the goal to blend the repairs so well, they become invisible; while making sure the process used will not damage, ruin or deface the original masonry assembly.

The reason why I do masonry, speaking for myself, of course, is to make it into a form of art. At my company, our skillset lays in reversing the unwanted effects of time — or of previously poorly performed repairs — on the masonry building envelopes of older structures.

And while we’re at it, we also aim at creating as-near-perfect-as-possible, glitch-free experiences with our clients so as to have elated customers as a result.

Based on my observations, that approach seems more valuable to consumers than purism pursued for its own sake.

Toronto residents: www.invisibletuckpointing.com

For anyone else: www.brickworkpreservation.com

Friday, January 3, 2014

The Big Question

You are the owner of a period home, perhaps Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian or Pre-WW2. It has been finished on the exterior either in brick or stone — or both.

In a utopian kind of a way, perhaps you should be saying “I want to restore it to its original condition”.

It’s one thing when the government is entirely subsidizing a project, and the individuals making the final decision feel a fiduciary responsibility to ensure the work will last several generations; but it’s another matter entirely when the adjudication has to filter through the many priorities we’re all personally facing.

But that can create problems, as a beautiful period dwelling, which was simply is need of maintenance, can become defaced (see picture); the cost being the lost of its vintage character — a plight that’ll be passed along to all future owners of that property, I might add.

For this very reason, there are homeowners who want to avoid such disasters and proceed more carefully, seeking out contractors who specialize in historic masonry. And these companies will tend to propose the longer term options, being what seems logical to them based on their experience and education.

The right balance, in my opinion is to offer what I call a “minimum viable standard” in the residential market.

This constitutes a recommendation to only deviate from the ultimate standard in ways which will potentially not make the repair last as long, but ensuring that whatever is done will not cause damage to the historic fabric, or ruin its aesthetic qualities.

Furthermore, there is also the question of intrusion. Wrapping up the entire house in scaffolding for an entire summer, while removing thousands of bricks and all the mortar joints of the structure, generates noise and a ton of dust. It tends to ruins landscaping and other valuables. It might necessitate re-painting most wood trims. You and your neighbors can’t leave windows open during that time. It clogs up the A/C system unless the latter is sealed and therefore unusable for a period of time.

In other word, there will be intrusion to a lesser or larger degree, and minimizing it can go a long way to improve your peace of mind as well as maintaining harmonious relations with your neighbors.

This may not be something you personally care about, but I have found it to matter very much to most of my clients.

This is why, we personally put a lot of emphasis, at Invisible Tuckpointing Ltd., my Toronto-based company, on keeping the job site as immaculate as possible during the project and upon its completion.

So ‘the big question’ might be posed as “How can I get performed what needs to be done affordably, yet properly, but without going overboard, while minimizing disruption for our family as well as our neighbors?”

Toronto residents: www.invisibletuckpointing.com

For anyone else: www.brickworkpreservation.com

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)